Reexamining How We Build and Operate Networks [Archived]

OUT OF DATE?

Here in the Vault, information is published in its final form and then not changed or updated. As a result, some content, specifically links to other pages and other references, may be out-of-date or no longer available.

University of Pennsylvania IPv6 Case Study

IPv6 will eventually replace IPv4. However, during the transition, institutions and enterprises that deploy IPv6 won’t typically be able to start sunsetting support for IPv4 right away. So, while a valuable benefit of deploying IPv6 is the reduction (and someday elimination) of demand for IPv4 address space and network infrastructure, it will be several years before IPv6 operators will fully realize that benefit. Fortunately, implementing IPv6 does not have to be especially difficult, costly, or disruptive. IPv6 can be deployed incrementally and even opportunistically. That is how we have been doing it at the University of Pennsylvania.

The three main reasons Penn decided to adopt IPv6 were:

The three main reasons Penn decided to adopt IPv6 were:

-

It has been clear for a long time that exhaustion of the IPv4 address space would become a significant challenge, and we did not want to be caught unprepared.

-

We wanted to support researchers at Penn who were interested in studying advanced networking, including IPv6 back when it was considered “advanced.”

-

We were fortunate to have the opportunity and wherewithal to be an early adopter in the space, and wanted to help drive demand for IPv6 support among our vendors and service providers.

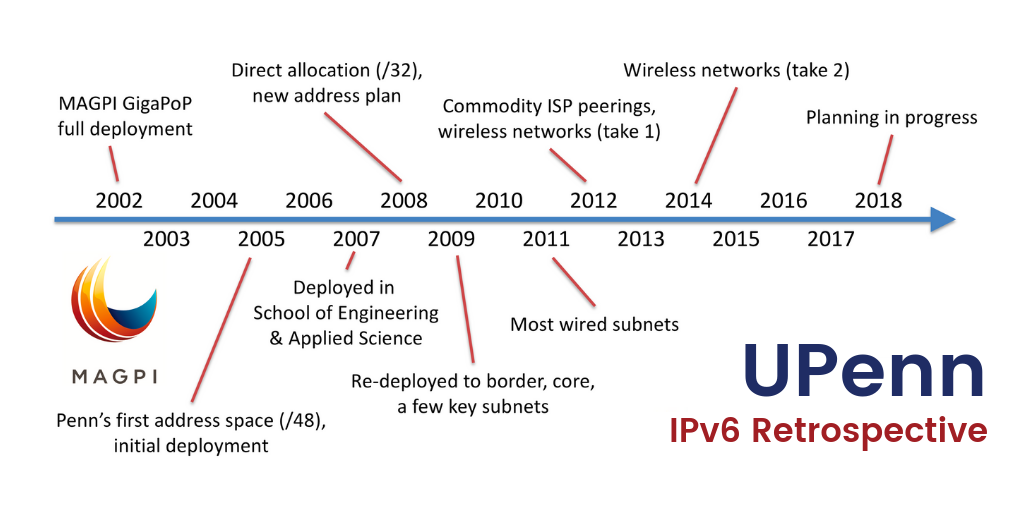

Allow me to take you on a whirlwind tour of Penn’s IPv6 deployment journey so far. It is a journey that started about twenty years ago, out past the left side of this timeline. The first edition of an IT strategy document called PennNet-21, laying out a vision for Penn’s enterprise data and voice network for the 21st century, had this to say in July 1998:

The first edition of an IT strategy document called PennNet-21, laying out a vision for Penn’s enterprise data and voice network for the 21st century, had this to say in July 1998:

“It is our hope that by being early adopters, we can help other sites see the benefits of transitioning to IPv6. It will also take us a significant period of time (at least 4 years) to transition all of the campus to IPv6.”

The authors of that strategy have been proven right about at least one of those things.

One of Penn’s first concrete steps was in 2002, when Internet2 reallocated a /40 of IPv6 address space to MAGPI, a regional GigaPoP Penn still operates today. MAGPI deployed IPv6 throughout its network and made IPv6 connectivity available to its members. In 2005, MAGPI reassigned a /48 of IPv6 address space to Penn, and we completed an initial deployment to a few networks.

Within the University’s federated, decentralized structure, Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science was among the first of its schools and administrative centers to embrace IPv6, and in 2007 deployed it on SEASNet. Anticipating the desire and ability to establish IPv6 connectivity (peerings) with commodity Internet service providers, and to route IPv6 traffic beyond MAGPI and Internet2, Penn obtained a direct allocation from ARIN, a /32, in 2008. Along with the new, provider-independent address space, came the opportunity to write a new address plan, which we did.

About a year later, we had re-deployed IPv6 to the PennNet border, core, three infrastructure server networks, and some central IT staff subnets. A few key services, like DNS, NTP, and Jabber were available over IPv6, and a number of additional servers had IPv6 connectivity for management via SSH.

Through steady progress over many months, we succeeded in provisioning IPv6 connectivity for somewhere between two-thirds and three-quarters of all wired subnets on campus—roughly two hundred altogether. In some cases, groups would ask to be excluded because of known or expected incompatibilities. And in a few cases, something went wrong, and we rolled back.

In 2012, Penn participated in World IPv6 Launch Day. We established an IPv6 peering with one of our two commodity ISPs and made the main Penn website accessible via IPv6 with the help of our CDN vendor. We turned up a second ISP peering about two months later. [At this point I would be remiss not to say a quick thanks to ARIN’s European counterpart, RIPE, for the historical routing table data that helped me to pin down some of these dates.]

That year was also when we first tried to deploy IPv6 to our wireless networks. Unfortunately, another wireless feature was not yet compatible, and we had to back out. After upgrading firmware on the wireless controllers in 2014, we tried again to enable IPv6 connectivity on wireless, and this time it stuck.

Penn still has work to do to continue our deployment and to promote adoption of IPv6, but when I look at how far we have come, and at the benefits Penn already enjoys, I am sure that the authors of that strategy document twenty years ago would be pleased.

Taking a gradual approach

A notable advantage of Penn’s approach to deploying IPv6—gradually—is that the need for dedicated investments has been rare. Almost without exception, Penn has added IPv6 support and capabilities as part of the normal technology refresh cycle. One of the significant types of decision has been when to shift IPv6 support from a nice-to-have to a must-have feature for each of the items in our IT portfolio.

Most of Penn’s investments in IPv6 have been in the form of labor costs to enable, configure, and operate available IPv6 features. Key decision-makers along the way were Senior IT Directors in the schools and centers, and those in the central IT group with responsibility for network infrastructure and network services.

IPv6 is like any other technology upgrade

We found that the most common obstacles were cases in which the feature support we needed for IPv6 was not ready for production deployment. The way to overcome such obstacles is a mixture of patience and determination. We make sure that our vendors and service providers know that IPv6 is important to us, and we try to work around the limitations of the day when possible.

Keep in mind that IPv6 is like many other technologies we find on our campuses. Think about other technology transitions you may have worked through in the past or may have to work through in the near future: SSL 3.0 to TLS 1.0 to 1.1 to 1.2…; 802.11a to b to g to n to ac…; Solaris to Linux; on-premises to cloud providers; and so on. There are invariably leaders and laggards, trade-offs and work-arounds, and sometimes sprints or slogs.

Finally, training for networking staff and systems administrators, along with advocacy across the organization have been key parts of maintaining momentum behind deployment of IPv6 for Penn.

Designing better networks

During the IPv6 EDUCAUSE panel I was a part of in late October, Brian Jones of Virginia Tech made the point that “it is a mistake to assume that IPv6 is just like IPv4”. I think this is a point worth expanding on and emphasizing.

Many practicing network engineers today have worked mainly or exclusively in environments where a publicly routable IP address is an exceptionally scarce resource. Consequently, a number of network design patterns that came into popular use over the last 20–30 years have been strongly influenced by IP address scarcity, and these are now widely taken for granted. We need to reexamine the way we build and operate networks as the world transitions to IPv6, because one of the most profound differences is that an IP address will never again be a scarce resource. IPv6 will enable us to design better networks.

When might we consider IPv6-only networks?

I have reason to believe that IPv6-only networks will start to become commonplace well before the majority of the world has connected to the IPv6 Internet. They may not turn out to look like you would expect.

There are two scenarios where it is already possible in some environments to implement an IPv6-only network, or it will be within a year or two.

-

Self-contained or isolated networks where all nodes are under common administrative control, and do not require arbitrary Internet connectivity, such as infrastructure management, AP-to-controller tunneling, and inter-component interfaces within applications and network services. Any need that might otherwise be met with RFC 1918 private addresses without NAT seems like an excellent candidate for IPv6-only operation. It would help avoid contention for private addresses in large institutions, address-space collisions in distributed environments and when integrating with cloud service providers, and associated complexities in adjunct network data systems like the DNS.

-

Networks with end-points that are tolerant of translation or proxy connectivity are good candidates for an “IPv4-as-a-service” model. For example, I am hopeful that DNS64/NAT64 will become a viable option for production deployment in 1–3 years, based on reports of success at scale from T-Mobile and preliminary experience at institutions such as the University of Hawaii. This model is particularly promising for address-dense use cases like a campus-wide wireless network or virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI) cluster.

Where to start?

Some might suggest starting with public-facing applications, but large or business-critical applications could also be among the most challenging candidates for the transition to IPv6. Instead, think about starting with Internet connectivity for user endpoints, such as PCs and mobile devices, while providing the minimum number of supporting services needed to enable dual-stack operation—at the extreme, a DNS resolver service that is capable of resolving AAAA records, even if it only has IPv4 connectivity, is sufficient to enable endpoints configured through SLAAC to access resources on the IPv6 Internet. It is possible to deploy this dual-stack connectivity one subnet at a time to manage risk and build familiarity. After establishing a base of IPv6-connected users, there will be more reason to deliver additional services and applications via IPv6.

Network-centric applications, like NTP and DNS, and applications that are commonly hosted partially or entirely by a vendor, like web or email, are likely to be good candidates for early IPv6 deployment work on campus-wide or public-facing components.

Not an all-or-nothing proposition

Deploying IPv6 is not an all-or-nothing proposition. An effective way to manage costs and risks, and to develop skills and confidence, is to deploy IPv6 in small, manageable steps. This applies at all scales, from an institution’s entire IT portfolio down to a single service or application. To illustrate this point, consider that a DNS deployment could be evolved to support IPv6 in multiple, independent increments, as outlined in the following table.

| Capability | Requirements |

|---|---|

| Support AAAA resource records | DNS server software supports AAAA internally |

| Resolvers accept client queries on IPv6 | IPv6 connectivity to the client Client has IPv6 resolver address |

| Replicate zone data on IPv6 | IPv6 connectivity from secondary to primary |

| Manage and monitor on IPv6 | AAAA record for the management interface |

| Publish zone on IPv6 | AAAA record for the authoritative server |

Parting thoughts

IPv6 is not optional. The longer it takes to complete the transition, the more opportunities will be missed to avoid the challenges and costs of coping with IPv4 address scarcity.

It is too late to be an early adopter. It is a great time to embark upon the transition to IPv6. We are all in this together.

Any views, positions, statements or opinions of a guest blog post are those of the author alone and do not represent those of ARIN. ARIN does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness or validity of any claims or statements, nor shall ARIN be liable for any representations, omissions or errors contained in a guest blog post.

OUT OF DATE?

Here in the Vault, information is published in its final form and then not changed or updated. As a result, some content, specifically links to other pages and other references, may be out-of-date or no longer available.