A Beautiful Way to Run the Network [Archived]

OUT OF DATE?

Here in the Vault, information is published in its final form and then not changed or updated. As a result, some content, specifically links to other pages and other references, may be out-of-date or no longer available.

Communicate Freely IPv6 Case Study

Communicate Freely in Port Perry, Ontario has 100% IPv6 availability to all customers. As the founder of the company, I made an executive decision to deploy IPv6 because it’s the right thing to do. As the only shareholder at the time, I didn’t have to convince others with an immediate return on investment and was able to make the decision on its technical merits. We wanted to be part of the solution, not part of the problem. The business justification I’m using now that the business has grown, is that we are going to have do this to at some point, so why not do it now instead of scrambling at the last minute? That justification works in nearly any organization – this is inevitable, so start making the changes sooner while the risk is lower. Right now, if I break IPv6, no one notices. When IPv6 becomes mission critical, I know everything will work just fine since we will have been using it for years.

100% IPv6 availability

We are a small telecommunications service provider consisting of 10 employees, 250+ fiber to the home internet customers, and 800 PBX phone customers. Everything we do including our website, email, office, and Internet service is dual stack. All our core services are either dual stack or IPv6-only. Every Internet customer we provide service to can get IPv6.

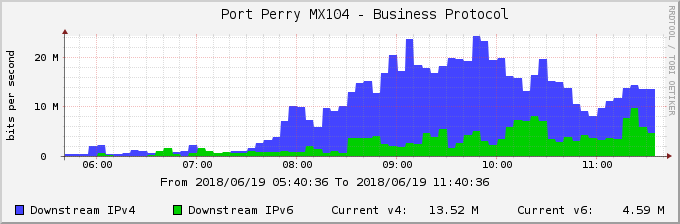

When we provide residential fiber to the home, our customers get an optical network terminal (ONT) which is the device the fiber connects to. Most customers use that device as their router as well, so when we turn on IPv6 in the ONT, they have dual stack for their whole house. Some people will use their own router, and if it’s old, it may not support IPv6. I’d say at least 50% of our customers have taken a prefix delegation, and they are connected to our IPv6 network. Right now, our traffic is 20-25% IPv6, and I am trying to push that up. Below is a graph from our router showing IPv4 vs IPv6 traffic. It’s certainly not at parity yet, but we can see that IPv6 traffic is becoming significant. On some days, I have seen IPv6 traffic exceed IPv4 traffic for brief periods.

Every now and then we see our traffic drop and I’ll wonder what went wrong. Maybe there’s a kink in our new DHCP server, or some other service isn’t functioning properly? Even if no one complains, I’ll fix whatever problem it might be. I have a laptop on our test bench plugged into a test ONT with IPv4 turned off. I can check the weather, play a YouTube video, etc. Every now and then I like to completely disable IPv4 and see what works and what doesn’t. With DHCP working correctly, the network assigns the DNS servers and all the things you need for the network to work. Everything site that is IPv6-enabled works just fine.

I have identified 4 key pieces of our IPv6 readiness for ISPs:

Getting your allocation from ARIN

Believe it or not, we’ve had our IPv6 allocation longer than we’ve had IPv4. When ARIN was getting close to exhaustion, I had to show I was using at least a /23 to justify my IPv4 request, but I couldn’t find an upstream provider who had enough space to sub-assign to me. The IPv4 address pool was already that constrained. I had customers ready to sign up, but our network only had an IPv6 allocation, so at first we NATTED everybody in IPv4 and gave them native IPv6.

Ensuring IPv6 support in the network equipment itself

A lot of equipment in our core supported IPv6 with no problems. Access equipment like our Fiber OLT mostly supported it, but customer equipment like ONTs, modems, routers and telephone end points would say they supported IPv6, but then when you went to use it, it wouldn’t work. It was missing a piece of functionality or didn’t configure properly. Only about a month ago could you finally create an IPv6 firewall rule in the latest firmware on our fiber ONTs. You could connect to the IPv6 Internet, but you couldn’t allow any traffic to come in. If you wanted to run an email or web server there was no way to allow that traffic through the firewall inbound. They had all the port forwarding in IPv4, but did not have an IPv6 equivalent. Finally, in the last two months, equipment vendors have reached a level of maturity in the software on the customer end points where it has the equivalent functionally to IPv4.

IT staff learning how it all works

Honestly, IPv6 basics aren’t that hard. Figuring out how to do it at the service provider level was more of the challenge since there wasn’t a lot of information out there and we were the first ISP in our area to have IPv6 deployed. Figuring out DHCPv6 took me some time, but eventually I got it to work. It ended up being a lot easier than I thought it would be. I poked at it a lot and experimented. Eventually I found some documentation from someone who had done something similar enough that led in the right direction. What I really needed to see was a config file, and to know what do I actually set this to in my network? What really made everything work properly in IPv6 for me was when we deployed a new open source DHCPv6 server called Kea, by the Internet Service Consortium. I think the older DHCP version we were using had some bugs in its IPv6 implementation. The software was supposed to do it, but there were little bits of functionality not working right. The router has to do DHCP relay in order for that to get passed to the server and then it has to be aware of what allocations have been given to the customer so that it can forward traffic properly. This is something that was not required for a typical IPv4 deployment, but with IPv6, the edge routers need to add routes for the address space assigned behind each customer router.

Having support for IPv6 in end point customer devices

The biggest barriers to IPv6 adoption we faced were vendor issues, especially customer premise equipment (CPE) like residential routers that couldn’t do IPv6. Or for example, in the ONT, IPv6 was turned off by default, so I had to go in and turn it on in all of them when we first installed it, and every time it reset. However, in a later release our vendor added some features where I could create a profile that will allow IPv6 to be on by default. Once that happened, and after the upgrade, we saw a significant increase in customers using IPv6, and a corresponding increase in traffic.

I think vendors need to step up. No product should be designed or sold that doesn’t support IPv6. If you’re a vendor or software developer you should be supporting IPv6 in all your products.

Future proof your network

My hope is that if we can have everything working well in IPv6, when we exhaust the /22 of IPv4 that we have, then maybe we won’t need to buy addresses on the secondary market. In our lower tier packages, we can provide an IPv6-only connection, and use a NAT64 translator to reach the remaining parts of the IPv4 Internet. Things will still work fine for most users, and we can look at IPv4 as an optional service for businesses or specialty users that need to support the older technology. IPv6 is future proofing our network. It will save us some long-term costs, and keep our network on the leading edge.

Benefits of using IPv6

As a network engineer, I’d love if we could get to the point where I could just not deal with IPv4 anymore. Private address space is pain, NAT is a pain, and I’d rather just use IPv6. I’m slowly reducing what I put on private IPv4 address space and use IPv6 only instead.

We have database servers and internal websites that don’t even have an IPv4 address. We just don’t have to manage that. If we need to allow remote access for people outside the network, we have firewall rule verses tunneling and NAT. We just let people in with a simple rule set as opposed to a more complicated solution.

I am OCD when it comes to numbers, and IPv6 is a lot easier to manage than IPv4. For example, if you are using private address space you have to make sure they don’t overlap with other networks you may connect to, or within your own network. Because we have to turn on IPv6 anyway, why not just do the one instead of both? It’s easier to manage one protocol than two. I think IPv6 is easier to work with because the subnets are bigger and everything is unique. If I assign a /64 to a subnet, I know I will never outgrow it. Whereas with IPv4, I have to always make it just big enough, because we are limited to the number of addresses we have. Another bonus with IPv6 is that everything is on the same boundary verses in IPv4 where you have to have subnet boundaries in the middle of blocks. I can take whatever byte position that is and increment it so I can make that line up with VLANs or other non IP things that are in the network. You can be a lot more orderly with your address management, because you are not tied to a constrained address space.

At the end of the day, all the things that are working on IPv6 save me time. I believe the customer experience will be improved in the long run as well. When everyone runs out of IPv4, we won’t be translating. In some cases, latency is lower on IPv6 so content loads faster. This is a performance benefit to using IPv6 that is small right now but will increase.

IPv6 is a very elegant protocol and easier than everyone thinks it is. Do it because it’s a beautiful way to run the network and don’t be afraid of it. If everyone would just do IPv6, every network administrator’s life would be so much easier, and the longer we put it off, the more ugly the Internet will look in the meantime.

Any views, positions, statements or opinions of a guest blog post are those of the author alone and do not represent those of ARIN. ARIN does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness or validity of any claims or statements, nor shall ARIN be liable for any representations, omissions or errors contained in a guest blog post.

OUT OF DATE?

Here in the Vault, information is published in its final form and then not changed or updated. As a result, some content, specifically links to other pages and other references, may be out-of-date or no longer available.